Everything you need to know about stem cells

What are stem cells, and what makes them so unique? What are the different types of stem cells, and how have they impacted modern medical science? Here is us answering all your questions about stem cells.

The word ‘cancer’ can be debilitating for most. Globally, one in six deaths is due to cancer, which means each one of us runs a good risk of being diagnosed by cancer, or of being closely acquainted to someone who has received a diagnosis, at some point in life. Once diagnosed, an individual has a vast array of choices, from surgery, to radiation, to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. With the growing studies in cancer genomics, personalised medicine may very soon hit the markets too, where drugs will be tailored based on the unique genome of the patient. Considering all these parameters, the patient would be required to make some very tough choices and the basic understanding of cancer at the cellular level may come be very helpful, not just to combat the disease but also to take responsible preventive measures.

So, what is cancer and why is it such a big deal? How do cells, that after-all is a part of your own body, go so out of control that it can turn against the body that contains it? To understand this disease, let’s take a look at the life story of the cell that grew into a solid tumour (which are those that occur is organs like the breast, lung, brain, liver and so on) and finally into a cancerous lesion.

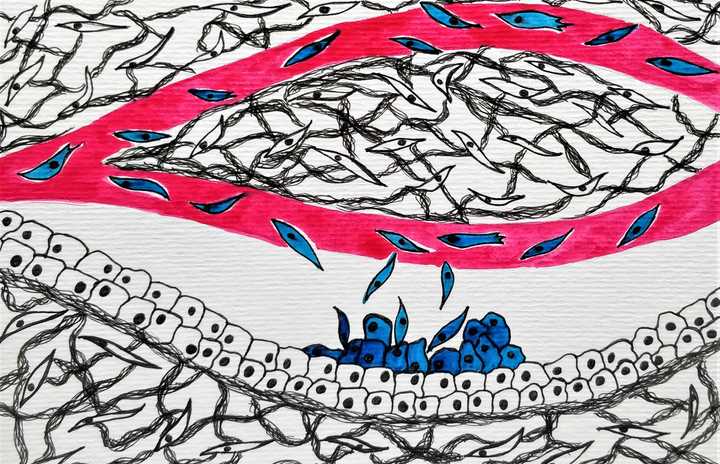

A tumour begins from that one cell that accumulates too many unrepaired mutations. Tumour cell in blue surrounded by a proteinaceous microenvironment. Blood vessel is red. © Sunaina Rao.

The human body has trillions of cells, all faithfully carrying the exact same piece of a DNA sequence. This sequence is of greatest importance as it controls almost everything the cell does. On receiving signals from the outside, it initiates a process where the DNA copies itself and diligently passes on the copy to the next cell.

However, this process is not error proof. We are constantly exposed to physical and chemical agents called carcinogens, which can introduce errors, called mutations into the sequences. The errors can be big, where huge portions of the DNA are deleted, duplicated or repositioned, or it could be a small change in its sequence, restricted to a single gene. The cell, however, has an entire tool kit when it comes to these errors. A strictly regulated repair machinery patrols the DNA, checking for and correcting mistakes. If an error goes beyond repair, the cell kills itself, a very important process called ‘apoptosis’. All in all, the cell can be a true martyr and thinks more for the organism that harbours it, than its individual self.

But the real problem begins when there are just too many mutations, that it becomes impossible for the repair machinery to correct all of them or if for some reason the repair machinery falters, and these errors go unrepaired. The mutations now get passed on to the next cell and this can easily lead to a snowball effect, where mutations begin to accumulate, making the DNA extremely unstable. Mutations can also be inherited. Here they exist passively, like a ticking time bomb, waiting for the mutational burden to increase, to blast away. This genomic instability is the cell’s first step in becoming cancerous (Stratton et al., 2009).

The tumour progresses by rampant, uncontrolled division of cells. © Sunaina Rao.

So how does this cell progress to a full-blown cancer? Not all mutations necessarily cause a cell to become cancerous. Most are just passengers, enjoying the ride. It’s the driver mutations that cause serious trouble.

For a cell to divide, it first needs to receive signals from its outside environment. If a mutation makes the cell more sensitive to such signals, it begins to divide even when it doesn’t need to. Additionally, cells also have certain breaks. These breaks are called tumour suppressor and they restrict the cell from dividing. Mutations that disable the functioning of such genes again can lead to the same consequence. Most cancer cells have a combination of such mutations and this can easily lead to uncontrolled, rampant and catastrophic cell division. At this point we can call this growth a tumour. As the growth is progressive, but still restricted to the point of origin, it isn’t cancerous…yet.

In the midst of all of this, let’s not forget that these tumour cells are not alone in this affair. Cells are always surrounded by a microenvironment (Bissell and Hines, 2011) which comprises of a milieu extracellular proteins and an assortment of cells that act as partners in the crime. The tumour cells are never isolated, they constantly exchange signals (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011) with their microenvironment, secretly conspiring.

Once the cell load increases, they recruit blood vessels to their aid, escape from their tissue confines and move into the blood stream, searching for a more comfortable home. © Sunaina Rao.

Let’s quickly remember here, that blood vessels navigate through intricate tissue spaces but can only supply resources to a set number of cells. So, what happens when cells go out of control? Where do they derive oxygen and essential nutrients from? Plus, there really isn’t enough space for the cells to go on dividing. It’s a dreadfully stressful situation – no space, no oxygen and no food. But again, cells have numerous tricks under their sleeve! They secrete factors that can recruit near-by blood vessels to branch and make more blood vessels. A process called angiogenesis. The tumour cells are truly masters of their trade and can be self-sufficient…but only to a point.

The reckless growth eventually reaches a point where things get too congested. So, what do you do when the room gets too crowded? You move out, in search of more enriched spaces!

But its not that easy to move when you are an attached, immobile cell. The cell is tethered to one another and to its surrounding protein rich environment called the extracellular matrix (ECM) by molecules that act like glue. So, to be able to move, the cell begins to modify its glue, wriggling its way out.

This however is again not enough. The proteins surrounding the cells can act like barriers, restricting its path. The cells have to become more mobile, similar to those cells that swim in the blood vessels. They also need to degrade those surrounding protein barriers. They make appropriate changes in their cellular structure to become more mobile and secrete enzymes that can degrade the protein mesh-work, through which they can now invade into their surrounding space.

On reaching a suitable site, the cells that painstakingly survive the journey, move out, interact with the microenvironment and establish a metastatic growth. © Sunaina Rao.

To be able to reach distant, nutrient and oxygen rich sites, the tumour cells need to access the well-connected highways of the body – the blood vessels. Once out of the confines of their tissue space, it’s not too hard to find near-by blood vessels, make associations with the endothelial cells that line the blood vessels and enter into the blood stream, a term called ‘intravasation’. To be noted here, is that the tumour cells can now be called ‘cancerous’ cells as they have moved out of the confines of their region of origin.

What now? They swim, alongside the huge assortment of cells, proteins and other molecules that flow in the blood stream. This however is not a joy ride in any way. There is immense mechanical stress. The cells collide with each other and in a traffic like this, accidents are inevitable. Additionally, these cancer cells are not used to swimming, they are programmed to be attached and immobile. In this panic stricken, stressful state, most cancer cells die. The fittest however survives and makes its way to far away locations.

On reaching a suitable site, which could be any near-by or distant organ, the cells move out of the blood vessel via a process called ‘extravasation’ and try to establish a new colony called a ‘metastasis’ in their new home, which is called the ‘metastatic site’. This again is a challenge. The new home may not be very inviting. For cells to establish a successful metastasis there needs to be significant interaction between the cancer cells and the microenvironment of their new home. If successful, the cancer cells settle down in their new home (Nguyen et al., 2009) and grow on to be full blown metastasis and that completes its long tiring journey.

A suitable therapy for cancer is mainly decided based on what stage the cancer is, in its journey. Milder treatments suffice if the cells haven’t moved out of their region of origin and harsher treatments if they have started to move out. The tricky part is that it is very difficult to know if the cells have dispersed into the blood stream and more importantly, some cancer cells may become resistant to therapy leading to a more invasive disease. The whole cascade of events that occur during carcinogenesis depicts a battle between individual cells and the multicellular body, a tug of war of sorts (Trigos et al., 2018). Perhaps as long as multicellularity exists there will always be a conflict of interest between the multicellular organism and the individual unicellular entities it harbours. So, perhaps as long as multicellularity exists, cancers will always exist.