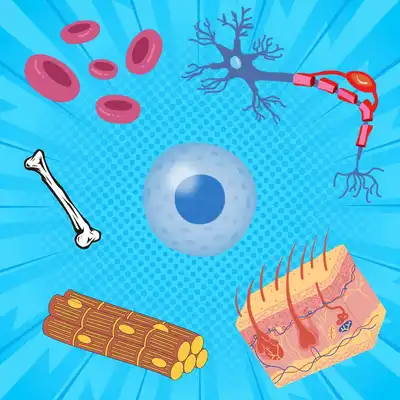

Everything you need to know about stem cells

What are stem cells, and what makes them so unique? What are the different types of stem cells, and how have they impacted modern medical science? Here is us answering all your questions about stem cells.

You have had a long tiring day at work and it is way past your bedtime. As you return home, you jump directly into your warm, cosy bed and quickly drift off to sleep. Your muscles start to relax and your breathing becomes slower. Soon you enter into a phase of deep, calm sleep. However, a few minutes later you begin to experience something interesting. You start dreaming about incidents that occurred during your day. After a few minutes, the scene changes. You now see yourself being chased by a stranger. You feel yourself panicking. Your heart races as you run fast, trying to escape. As the chaser almost catches up with you, you wake up, only to realise it was all a dream. You breathe a sigh of relief and go back to sleep with the hopes of having a better dream the next time!

So, what happened here? You had actually entered a very specific stage in your sleep where you were experiencing vivid dreams. If someone had closely observed you, they would have seen your eyeballs move rapidly in different directions behind your closed eyelids. This stage of sleep is called REM sleep or the Rapid Eye Movement sleep.

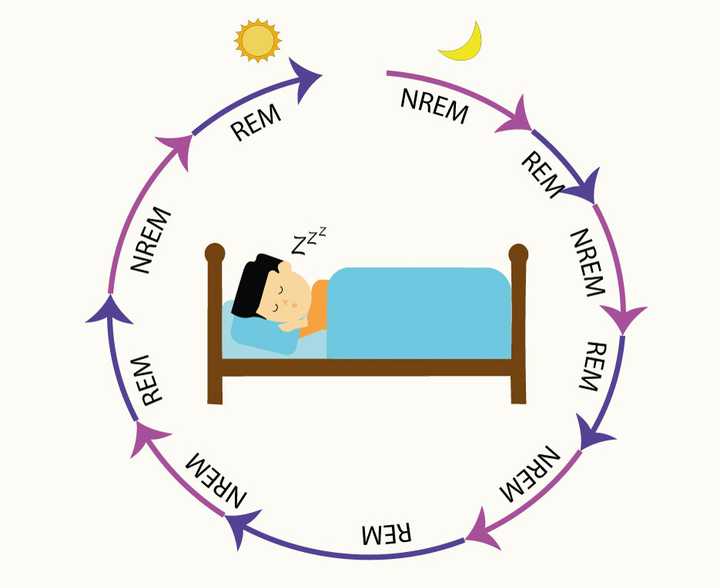

Alternating REM and Non-REM (NREM) sleep from the time of falling asleep at night to waking up in the morning. © Sunaina Rao

Sleep is a natural state where we lose consciousness. Our ability to respond to what is happening around us is also highly reduced. When the activity of the brain in sleeping individuals is studied, it is observed that sleep occurs in two stages - non-REM (NREM) sleep and REM sleep.

In healthy individuals, sleep begins with NREM sleep, where we slowly transition from being awake to a state of calm, deep sleep. Once this stage is completed, the next stage of sleep begins - REM sleep. Although this is a stage of very deep sleep, the activity of our brain is similar to that when we are awake. This is the stage where we experience dreams and our eyeballs move about rapidly behind closed eyelids (hence the name Rapid Eye Movement sleep). Thankfully, our muscles remain paralysed in this stage, preventing us from reacting to our dreams. However, we might experience some uncoordinated muscle twitches in this phase.

REM sleep is followed by a brief period of awakening. This is the point when we might realise that we were dreaming. In normal circumstances we would fall asleep once again, entering the next cycle of NREM and REM sleep. In a full night’s sleep, we could have several such cycles (Peever and Fuller, 2017).

But why did we evolve these sleep stages? More importantly, how is REM sleep and all the dreams that come with it helpful to us?

REM sleep has been a topic of interest for many scientists for several years now. However, we still don’t fully understand the use of this stage of sleep. To understand REM sleep a little better, a group of scientists studied the sleeping behaviour of jumping spiders - Evarcha arcuata (Rößler et al., 2022).

The jumping spider - Evarcha arcuata. Credit: [Wikimedia](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Evarcha_arcuata_04.JPG)](/static/0d8208b850076f72c88439e727fdf241/80e3c/Evarcha_arcuata.jpg)

The jumping spider - Evarcha arcuata. Credit: Wikimedia

They found that these spiders rested throughout the night by hanging themselves upside-down on a silk thread. The team was interested to see if these spiders also experienced REM sleep. They, therefore, decided to observe the sleeping spiders using an overnight infrared camera. To their surprise, they saw that these little spiders showed some rapid movement in their retinas (a structure in the eye), in specific phases of their sleep. This was accompanied by some uncoordinated movement of their legs. This was very similar to what happens in REM sleep in us humans.

Interestingly, these REM sleep sessions were followed by a brief period of awakening. During this period, the spiders adjusted their supporting web and cleaned themselves. This was similar to the brief period of awakening we experience after REM sleep.

In short, these spiders were sleeping just like us!

This study essentially shows that REM sleep is not unique to just us. In fact, spiders show similar sleeping patterns. Moreover, REM sleep has also been observed in many other animals like cats, mice, giraffes, reptiles, fishes and birds. This suggests that REM sleep must have some evolutionary advantage for us and other animals.

Many scientists strongly believe that REM sleep helps in strengthening our memory. This is because individuals who have been deprived of REM sleep show reduced memory formation. Also, since brain activity in REM sleep is similar to that of the awake brain, some scientists believe it might be helping us prepare our bodies for wakefulness.

Studies like this help us in understanding the importance of REM sleep, dreaming and sleep in general. Indeed, we may not be too far away from inventing technologies that help us enhance the quality of our REM sleep and the advantages that come with it. Studies like this also prompt questions like - If spiders have REM sleep, do they also have visual dreams like us? If so, what might these dreams look like?

While scientists find answers to these questions, let’s be warned about one thing - There is a chance we might be woken up by a couple of crawling spiders in our dreams tonight!