The Simplicity of Everything

A concise introduction to cosmology and the theory behind it.

Perhaps there aren’t so many mysterious and yet fluent concepts such as infinity. Most of us have some sense of it, even as children. And yet, trying to pinpoint it can quickly become philosophical or metaphysical. As children, we might say “I love you infinitely” to a parent or a sibling to express endless love, or perhaps express the desire for “an infinite number of cookies”. One might try to express the infinity of the universe, the spirit or the human creativity, or even the infinite number of music pieces that may be composed.

It isn’t much to see that those examples actually deal with very different concepts, and yet have some kind of resemblance. Each of them somehow treats some kind of amount, whether tangible or not. And that is the subject of this little article: infinity. Though here it’ll be in a mathematically precise fashion, that most haven’t seen, I believe.

From high school to undergrad, outside mathematics, one learns about the symbol that appears as some kind of “real number,” perhaps accompanied by some algebra rules for summation and multiplication, in order to express a “really large number, or amount”. This way of talking about it is actually very well-defined (mathematically speaking), but not what I’d like to consider in this piece. Here I’ll talk about the way one can count. Yes! 1, 2, 3… Like in “1 dog, 2 cats, 4096 rabbits, mice.”

There is a clear infinity there: the infinite number of numbers. We learn it in math as the set of the naturals, . The nice thing about it is that, even though you never stop, one can put an order to it and, you know, count its elements. And from that we have some kind of definition of one concept of infinity. It even has a name: countable. We say that any other set is countably infinite, or simply countable, if it has the same size as the .

But what is “size”? Well, that’s the hard question. Even though size is a tough concept, a mathematician usually knows how to compare sizes, using functions. Yes, the same thing we learn in high school and is a nightmare for many. The one that reminds us of quadratic formula and graphs smiling or frowning. But stay calm. Pretend there is a hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy and DON’T PANIC!

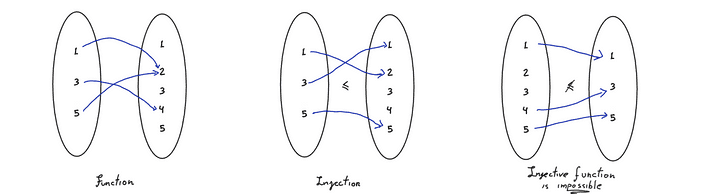

The following are formal definitions. But don’t digress so much about it, it’s just so we can agree on things. Read the following in a sullen, and kind of annoying, voice of an old scholastic man, way behind his time.

“A set is a collection of elements, which are well-defined. Another set is a subset of , if every element of also belongs to , denoted as ”

“A function is a relation between two sets, and , such that for each element of is related to only one , so called the image of by , denoted .”

“A given function is called an injective function, or simply injection, if given in then in .”

Maybe visualizing stuff is better than defining them. A set is just a collection of anything: numbers, letters, functions, sequences or even other sets. We can think of functions as a collection of arrows relating two sets with the following rules: every element of the origin set has to have exactly one arrow coming out of it; if the function is injective, no element of the target set has more than one arrow pointing to it.

From left to right, set-arrow representation of two possible functions A → B, in which the second is an injection, and the third showing the impossibility of constructing an injection B → A, that happens because B is in fact larger than A. © Hermano Farias.

So, how do functions help? Well, the set , which has 3 elements is smaller than the set of 5 numbers , which has 5. The number of elements is called cardinality, that we denote with the symbol , like in and , and is the central concept that we’ll use.

We see it’s possible to build an injection from to , but not from to , exactly because is in fact “bigger”, or as one says in the math lingo has larger cardinality.

Now here’s the kick. Given two sets to , if there is at least one injection , among possibly many, then automatically ! And if that is also true that , i.e. there is another injection , then we write . That is, and have the same cardinality.

Finally, there is a very “natural” quality in such a way to compare sizes, namely given that , that is, is a subset of , then , as in the example above.

Naively, one may think that a set’s cardinality is just a number, but that’s not really the case. We can talk about the cardinality of , which can’t be written as a number, because, well, there is an infinite number of numbers, and since we can’t give a number we just write it as . It is in fact the first and smallest infinity out there, called countable.

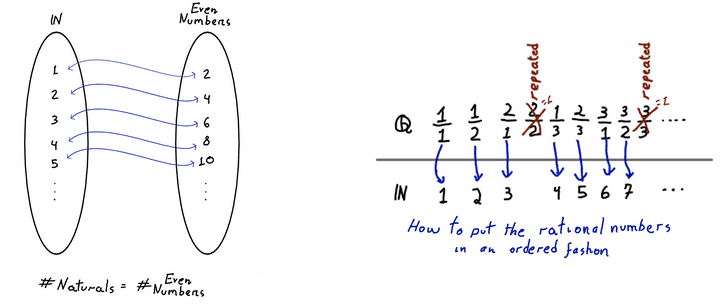

Are there other sets that are countable? Yes, plenty! The set of even numbers has cardinality even though there is only “half” of the number there (yeah, that’s right.). Or perhaps the collection of all prime numbers, which is a subset of , and yet has also cardinality (confused yet?), because there are infinite prime numbers. When a set has non-finite cardinality, it’s actually quite normal to find a subset with the same cardinality.

Maybe the reader already concluded that any set which can be put as an ordered sequence of elements that never ends is in fact countable (being those elements numbers, functions or even other sets). An example is the rational numbers , those that can be written as fractions. Well, , because , but there is also an ordering for the rational numbers, and it shows that in it’s also true that , and thus .

These sketches are visual proofs that the “number of even numbers is the same for all numbers” (notice the double arrows showing that you can go both directions) and how to order the set of all rational numbers, with no repetition. © Hermano Farias.

Now is there a set with cardinality larger them ? Yeah! Plenty, actually. But they can become very confusing, very fast. One of them is the real line , and is referred to as the continuum cardinality. The idea here is that one cannot put its elements in an infinite sequence. There is this cool argument that shows that’s true, called Cantor’s diagonal argument, that proves that in fact . It’s a bit long and beyond the scope of this piece, so I’ll let the curious take a look at it.

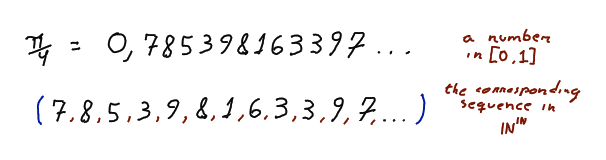

Just like the case , there are many subsets of ℝ with cardinality . One of them is , the set of real numbers between and including 0 and 1, which are decimal numbers that start with a zero, such as 0.78598163397… The way to relate is sketched below, but it might be difficult for the uninitiated.

![On the left, an illustration of the relation between the real line and the interval [0,1], with the non-trivial function. On the right, a sketch showing how to construct the cantor set, starting with the interval [0,1], seen as a segment, and removing parts of it, step by step. © Hermano Farias. Cantor set](/static/470799d6fe75250d72608726b22f2faf/37523/cantor-set.png)

On the left, an illustration of the relation between the real line and the interval [0,1], with the non-trivial function. On the right, a sketch showing how to construct the cantor set, starting with the interval [0,1], seen as a segment, and removing parts of it, step by step. © Hermano Farias.

It turns out that the set of all sequences of natural numbers, denoted , have exactly the same cardinality of , because a decimal number starting with a is written as an infinite sequence of natural numbers. So, even though is countable, the set of all possible sequences of numbers is not.

One represents a number between 0 and 1 by a sequence of numbers, just taking each number in the decimal representation and putting them in a sequence. © Hermano Farias.

The last example of a set of continuum cardinality is the Cantor set . Among mathematicians, it is considered a kind of wildcard, because it defies our intuition. To explain that it is, we begin with and take out of it the second third of it. Then for each remaining section, you take out the second third again. Rinse and repeat ad infinitum (look at the drawing above) and one ends up with . One may think one ends up with nothing, but there are many, many numbers remaining.

In fact, , even though it can be seen as a collection of dots with gaps between them, with no “volume”, that is, if one represent them as points on the line, no two points are connected with a segment. And there are so many, that one just can’t count them! You can’t order them and put them in a sequence.

To sum up, we have the following relation of infinity sizes:

Yes! The set of all functions from the reals into itself, denoted here as , has cardinality even larger than continuum. It is so large that not even an infinite and countable collection of lines would be enough to “count” them. I find this really weird.

The notation is not coincidental. For any set , one can denote as the set of functions of into itself. And it is always true that . So, for we have . We repeat the argument ad infinitum, and voilà! There is in fact a countable collection of infinities, one larger than the next. Let it sink a little. Math can be a bit overwhelming.

And with this final conclusion, I shall end this piece.

I know that some readers might be lost right now. Threat not, it isn’t a simple topic. Quite the opposite, in fact. If that’s the case, I invite the reader to revisit this piece after a period of digestion. One truthful fact about learning math is that sleeping on it really helps.

For those inflamed by all of this, I recommend the unassuming Naive set theory by Paul R. Halmos and The Joy of Sets by Keith Devlin. But be warned! It’s not for the faint-hearted, and certainly requires perseverance to conquer.